TIME OUT WITH…

Sarah Rose, author of D-Day Girls

By Bailey Beckett

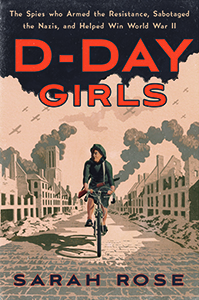

In her latest book, D-Day Girls, Sarah Rose unearths the untold stories of the women who helped turn the tide for the Allies in WWII behind enemy lines.

Sarah Rose, author

Sarah Rose, author©Maria Smilios

Not many authors would parachute from a plane, shoot guns, master French and learn Morse code for a book, but there are none like Sarah Rose. The New York-based writer, who once chronicled real estate dynasties for The Wall Street Journal, recently debuted her second novel, D-Day Girls, which is generating buzz (and sales!) for its you-are-there account of the women who helped infiltrate Nazi-controlled Europe and turn the war for the Allies. The book, published by Crown, follows the stories of three women sent behind enemy lines to “set Europe ablaze” by Winston Churchill: midnight air drops, sabotage, secret codes and commando raids that helped pave the way for the Allied victory on D-Day. It was debuted April 23rd and is available in bookstores nationwide, as well as online (prh.com/ddaygirls). New York Lifestyles talks to the writer about her two-year journey into the heart of one of the war’s untold stories.

What gave you the idea for D-Day Girls?

I wanted to know about the lives of the first women in combat. Focusing on the earliest class of women sent to France was a way to shine a light on the pioneers. Andrée Borrel, Lise de Baissac, and Odette Sansom were each, in their own way, instrumental in laying the groundwork for an Allied victory. Andree helped raise the Resistance on the Channel coast; Lise was in Normandy in June 1944 to lead it. Odette escaped from Ravensbruck, and the evidence she collected helped convict the leader of the largest women’s prison in history.

Andree Borrel, Lise de Baissac

Andree Borrel, Lise de Baissac©Wikimedia Commons

How long did it take to research and write? And what was it like to be in the UK and France to interview, meet families and be where these events happened?

I spent two years writing. As a starting point, I moved to France to immerse myself in the world of Vichy and to learn French. I wanted to understand the training these women had gone through, so I went parachuting, took a boot camp, practiced shooting, assembled a radio and attempted to learn Morse code. I would make a terrible spy, but I wanted to create a lived-in feel. I visited the known addresses and walked every step. I interviewed veterans, families, and scholars, who were so welcoming and gracious with their memories, but by and large, my research took place in the archives. I found an embarrassment of riches in diaries, oral histories, letters, war crimes testimonies and declassified military files.

What was the hardest part?

I needed to recreate clandestine work in France for readers but had to dig deep for information. A good agent leaves no trace, so operational details are invisible by design. Missions were classified for two generations, until the end of the Cold War. By that time, few agents were still alive. Files were selectively weeded long before declassification, particularly when details were embarrassing to the Allies. Some first-person accounts are grandiose and demand being taken with a great deal of salt; clandestine work attracts kooks, smugglers, and fantasists, in addition to heroes. Commanders had the paternalistic idea that what happened to women behind the lines was either unseemly for posterity, or grotesque. When agents got raped, records are silent. When Odette spoke about her torture, she was called a hysteric, despite her scars. Odette’s recruiter even spread the false rumor that she survived only because she was the Ravensbruck commandant’s mistress.

Why don’t people know this story already?

Sending women to war was brand new. When one-third of the recruits didn’t return it horrified Britain, and was seen as a betrayal of her most vulnerable citizens. Baseline sexism also distorts the record: Women’s missions were dismissed as “secretarial,” though they were telegraph operators, couriers, and circuit leaders: the same work performed by men. Sexual relationships blossomed behind the lines, producing a few marriages, but historians disdain this very human part of war as “romantic twaddle” and go back to counting bullets and bodies. The overwhelming reason we don’t hear about women in global conflicts is that until now war stories have been written by men.

Odette Sansom

Odette Sansom©Wikimedia Commons

Why should readers buy this book now?

The 75th Anniversary of D-Day will be celebrated this year on June 6th. I want the world to remember that the hidden figures of D-Day are women. We don’t know enough about the female leaders in Normandy and Brittany, or about the mothers and daughters who died receiving arms dumps, hiding contraband and forging documents, who were publishing manifestoes, conducting underground railroads, and defying Nazi torture. They are every bit the heroes men were, and, after 75 years, deserve to be honored.

What do you hope readers get out of this book?

Andrée, Lise, and Odette are inspiring. In a moment of global upheaval, their stories demonstrate what the anger and energy of politically-minded women can accomplish. With authoritarian, ethno-nationalist regimes on the rise, the world of D-Day Girls doesn’t seem so far away. But as in France in 1940-1944, women are now stepping up, taking to the streets, organizing opposition, putting their bodies on the line, and proclaiming their right to #RESIST. The work of our matriarchs reminds us that activism is a potent weapon and can change the fate of nations.

What is your next project?

I have no idea what’s next!