ENTREPRENEUR’S CORNER

By Elsie McCabe Thompson

What makes a true New York story? I grew up in Brooklyn and lived most of my life in Manhattan. Outsiders see New York City as one, big, continually moving organism, but those of us who were born here know it to be a collection of villages. To me, “community,” that hard-to-define sense of home-place and cohesion is critical. It is where we all feel connected to one another, not because we all know each other but because we value the same things, and that is where I always want to be.

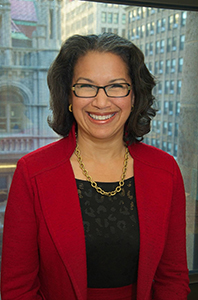

Elsie McCabe Thompson

Elsie McCabe ThompsonA FORCE OF NATURE

I am the daughter of an African American father, who was a physician, and a Latina mother. My mother could effortlessly talk to anyone, anywhere. As a child, her talks with complete strangers embarrassed me. Mothers like mine come in all colors and all ethnicities and they are all true forces of nature. Whether my mother was angling to get me into the best classes in school or chatting up a building superintendent to get me the inside track on a soon-to-be vacant apartment, she was resolutely determined when it came to finding the best for her children.

Throughout my childhood and particularly in matters that involved my schooling, my mother was my staunchest advocate. Later in my education, I was blessed with outstanding teachers and mentors who encouraged me and taught me to have faith in myself. Early on I struggled in school and it shaped my worldview as I witnessed my mother and a couple of teachers fight for me. But it begged the question: what happens to all the children who don’t have parents and teachers with the determination of Marine Corps fighters to advocate for them?

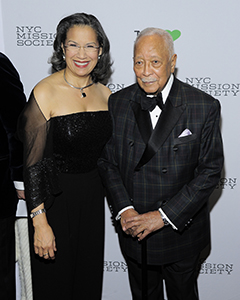

By the time I was in law school, I was working for Harvard Legal Aid. I was doing real work for people, and it mattered because it wasn’t just theorizing. I wrote letters for people who were sick and desperately trying to get Social Security Disability benefits. I helped organize the Somerville Housing Authority to help tenants fight for better living conditions. After law school, I worked for a large law firm, but on the very day that I paid off my last student loan, I quit and went into public service working for the city’s first Black mayor, David Dinkins.

Elsie w Peter Rabbit

Elsie w Peter RabbitA LIFE CHANGING EXPERIENCE

Mayor Dinkins was assembling a delegation to South Africa to help usher in the skills and the know-how to build the new South Africa. It was to consist of the international press corps and teams of people who were expert in affordable housing, educators to talk about setting up public education for students who had never been in school, and public health experts to discuss setting up healthcare delivery where there was no access to electricity. The delegation’s trip was to be privately funded. He needed someone to go there and help set up the itineraries and all the logistics. Although the initial funding could only pay for a one-way ticket for me, I was thrilled to go. It was truly life changing.

One of the most memorable experiences for me was meeting a man from a tiny black township called “Alex,” short for Alexandra, not far from Pretoria. He told me that people felt fierce pride in being from Alex. Whether they lived relatively well or were completely destitute, they had enough pride of place and enough of a feeling of community to come out every day and take care of Alex. He was concerned that their precious sense of community would be lost in the post-apartheid era, when a community might be more defined by income than commonwealth. That experience has always stayed with me.

I have lived in Harlem for many years. Harlem has that feeling of community and history that is unique. It is food and music and iconic civil rights leaders and brownstones, of course. But it’s also about the shared cultural values of bringing a plate to a sick neighbor, chatting with the storekeeper, patronizing the family-run restaurant, watching out for each other’s children and caring about their futures.

Elsie with Former

Elsie with FormerMayor David Dinkins

AN ADVOCATE FOR CHILDREN

When I became president of the New York City Mission Society, I had two important strategies: to be a fierce advocate for children and families who have no one else to fight for them and to maintain that same strong sense of community that is so important to me.

For the past several years, the Mission Society has been focused on making up the educational deficits that children are living through the trauma of poverty by providing programs that wrap around public school curricula. Our Power Academy program addresses the educational achievement gap through after-school enrichment and in summer camps. Through exciting hands-on activities, children concentrate on STEM learning and language arts, with special sensitivity to diverse cultures and new English speakers. We are proud that 84 percent of Power Academy kids show improvement, often by two or more reading levels.

I was able to launch a highly successful—and free—GRIOT (Global Rhythms in Our Tribe) program that teaches children to play instruments after school, where kids learn the math of music and the science of sound while they improve their math scores.

LEADING THE WAY

I’ve also been focused on our Learning to Work high school program, which works with more than 1,200 high school aged students who have either dropped out of high school previously or are unable to graduate because they have fallen too far behind—which we know would doom them to a lifetime of poverty. Through intensive engagement, we coach and encourage them toward that all-important diploma, while arranging paid internships, so they gain job skills. They leave the program ready for the world of work or to take the next step in their education. Many of our Learning to Work programs boast an 89% graduation rate, far above the citywide average.

Left to right Stan Rumbough,

Left to right Stan Rumbough,Jean Shafiroff, Elsie McCabe Thompson and Katrina Peebles

For all this success, I am keenly aware that we are reactive to educational deficits that might have been avoided in the first place.

Many young people may successfully graduate, but who will not live the best possible versions of themselves because their education was uninspired or because they just did not meet that mentor or role model who would lead the way. Nelson Mandela said it best: “There is no passion to be found playing small—in settling for a life that is less than the one you are capable of living.”

We owe it to our collective future as a city, and as a society to ensure that every child, regardless of background, gets a quality education with all the inspiration, we can pack into it. This is what motivates me every day, and I am glad that my early experiences have shaped my current outlook—that education is the path forward to success for students in their schools and in their lives.

For more information on New York City Mission Society, visit nycmissionsociety.org.