MY NEW YORK STORY

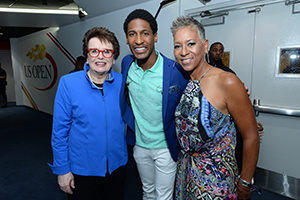

Katrina Adams Photo by Michael J. LeBrecht II

Katrina Adams Photo by Michael J. LeBrecht IIBy Lee Gabay

One of my many unofficial duties as a teacher is to find appropriate and inspiring speakers for our graduations. To do this, I gauge the collective personality of the graduating class, reflect on the cultural climate of the year, and then reach out to an individual I feel would be ideal for the June ceremony. Last year, within an hour of sending out a request, my ideal speaker wrote back with an enthusiastic “Yes!” And before long, she is standing before the 2017 graduating class of Brooklyn Democracy Academy, the transfer high school in Brownsville where I teach over-aged and under-credited students.

Katrina Adams, Chairman, CEO, and President of the United States Tennis Association (USTA) is encouraging the students to take positive risks towards their betterment, telling them, “Getting back up says more about you than being knocked down. Challenges reveal your character and can lead to greater growth!” Her words impact my students, many of whom have been incarcerated, homeless, or in foster care. She concludes her keynote by reminding them of the Michael Jordan Failure commercial, which famously told how his 26 missed game-winning shots ultimately inspired him to succeed.

Katrina Adams Courtesy of USTA

Katrina Adams Courtesy of USTAA MORE COLORFUL GAME

Taking hard shots and positioning others for success are two beautiful tenets of Adams’ personal and professional mission. A gifted athlete in her own right, she was the Illinois two-time state tennis singles champion and a two-time NCAA doubles champion. She reached the fourth round at Wimbledon in 1988 and has twenty WTA doubles titles. When her playing days ended, she coached the US National Team, did commentary for the Tennis Network, and then became the first African American president of the USTA. She was also its youngest president and the only president twice-elected. Beyond her elite tennis resume, she continues to foster equality and diversity within the game. “We want tennis to look like America demographically by making sure that we are connecting with every ethnicity in America to engage them in our sport,” she states.

Growing up in Chicago as the daughter of schoolteachers, Adams was taught to embrace differences and to take an interest in others. She seems to shrug off her early tennis achievements, which are remarkable, considering that she was one of the few urban African American females from a working-class family playing a historically white and wealthy country club sport in the 1970s. “There were certainly barriers back then,” she explains. “I was introduced to new environments and communities through the sport. There are always cultural differences, but as long as you are doing things in the right way, nothing else matters.”

Photo by Mike Lawrence

Photo by Mike LawrencePARKS & RECREATION

As an educator, I am always searching for ways to enrich the lives of my students. When I read about a panel discussion on how tennis can better serve diverse youth populations (and that Katrina Adams would be a discussant), I made sure to attend. Here I learned about the Harlem Junior Tennis and Education Program, on which Adams serves as Executive Director, and which brings tennis to youths from our city’s lower-income neighborhoods. Adams is proud that 90 percent of the students in her program graduate high school, in contrast to the citywide average of 67 percent. She believes the key to a child’s success is simply access and participation.

To further athletic opportunities, the USTA launched its youth brand, Net Generation. Net Generation is an initiative for kids aged 5 to 18 that offers coaches, schools, and parents customized coaching curricula to give young people a chance to learn and enjoy tennis on their own terms. “Parents are putting their kids into sports to be professional athletes, but we want kids in the game for the health benefits that it creates for their mind, body, and soul,” explains Adams.

Photo by Jen Pottheiser

Photo by Jen PottheiserGRAND SLAM

Two weeks later, I see Adams on TV standing center court at Arthur Ashe Stadium inside the Billy Jean King Tennis Center in Queens. A rare all-American women’s U.S. Open Final Four has concluded, and Adams is presenting the championship trophy to debut winner Sloane Stephens. Adams speaks to the event’s spectators, TV viewers, and the American finalist standing next to her, saying, “For me, I couldn’t be more proud to be here to see you, the future of diverse American tennis.”

The following evening, Adams is on center court once again. This time to give Rafael Nadal his Men’s championship trophy, further demonstrating that the U.S. Open also practices gender equality with equal prize money ($3.5 million) for both men and women.

Photo by Jennifer Pottheiser

Photo by Jennifer PottheiserHaving always digested a new nugget of wisdom in the presence of Katrina Adams, I wanted to share the important social justice work, which she champions, with a broader audience. When I asked her if she would sit down with me for this interview, she said, “Absolutely, Doc.” She invites me to join her at the National Association for Multi-Ethnicity in Communications annual conference in Times Square, where she is the recipient of the prestigious Mickey Leland Humanitarian Achievement Award. It is here that we speak about her life, legacy, and mission. During the Ceremony, former Mayor David Dinkins introduces her, referring to her as his “daughter.” Dinkins, who grew up during Jim Crow laws and has lived through the civil rights movement, says, “Each February I am asked if Martin Luther King’s dream has been realized. I always respond with a ‘not yet.’ But enormous progress has been made, and it is people such as Katrina Adams who furthers along that promise. And she herself is the fulfillment of that dream.”

As she was with my students back in June, Katrina Adams continues to be perfect in her role of elevating, inspiring and improving the lives of New Yorkers and so many others.

Lee Gabay is a doctor of Urban Education who teaches in Brooklyn, N.Y. He has written about education, incarceration, basketball and sneaker culture since 2006. His first book, I Hope I Don’t See You Tomorrow was published in 2016. He lives in the Lower East Side with his wife and daughter.